Both my parents were raised on farms in Nebraska often working someone else’s land for shares. During my childhood, my father worked in San Francisco as a foreman in a can factory, and my mother raised four kids and took in other peoples children for income. They chose to live in the city of Palo Alto, because of its public schools’ excellent reputation. Palo Alto had a middle-class white side and a black and brown East side; rarely did the two sides meet. Though I had few academic achievements in school, when I graduated high school I felt well equipped to understand the injustice of class and prejudice.

The artwork I created at Foothill Community College in the '60s did not reflect my developing political consciousness except for one ceramic self-portrait. It depicted an image of myself blackened with Napalm burns. On the pedestal beside the work stood my singed draft card. One semester after completing the sculpture, I left for Canada, a country not at war with Viet Nam and without a military draft. At my immigration hearing I was asked, “What is your profession?” I replied, “artist.” The border official smiled and stamped my application, “Rejected.”

In 1969, with the help of the Hayward State College soccer coach, I entered California State University, East Bay, to study art. Again, one semester short of graduating with a degree, and unmoved by the draft board threats of jail, I dropped out of college anxious to become a practicing artist.

In order to pay for art supplies and necessities, I began a series of what I thought would be temporary factory jobs. At each job I was welcomed to the turbulent shop floor by organizers fluent in Marxist economics and with a serve-the-people art philosophy–all new to me. These dedicated activists were Black Panthers, communist revolutionaries and trade unionists. I soon found myself in the role of shop steward and participated in unionization drives, contract negotiations and strikes. This practical art and class education still guides my work today.

— Doug Minkler

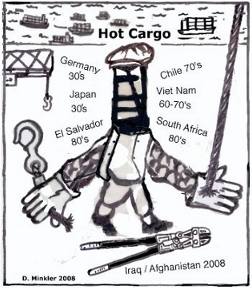

The continuing death and destruction unleashed by the United States following 9/11 and the media’s monolithic support for it’s violations on international law makes it imperative that independent artists create effective pointed alternative statements. Though the military aggression of the United States has been met with an unprecedented artistic response, it is our effectiveness I would like to address. I’ve come to realize that an important key to stimulating change in our society is the very task that I and most other political artists have avoided. We have become fluent in the language of death, destruction and alienation, but find ourselves limited when it comes to the language of peace, Internationalism and justice. The unrelenting barrage of governmental corruption, Nationalism and wars has kept us on the defensive; consequently, we have created little in the way of visionary art. Inspirational acts of compassion and solidarity, as well as examples of people fighting for justice and equality occur daily, yet are rarely captured in our work. It is these images of hope that have the power to create real change in our society.

Artists need to move beyond criticizing capitalism, toward illuminating successful, alternative models of social organization and cooperation. The doctrine of Internationalism can help guide us toward this end. This doctrine states that the common interests of nations are more important than their differences. By contrast, Webster’s Dictionary defines Nationalism as “The doctrine that one’s national culture and interests are superior to all others”. While Nationalists require blind allegiance to one’s national rulers, Internationalists see themselves as part of a global working class with allegiance to no country.

Examples of work reflective of Internationalist thinking include Food First an organization that believes in order to be free from hunger, people must have real democratic control over the resources needed to sustain themselves and their families. They offer educational resources from books to in-the-field assistance to those involved in the struggle to reform the global food system from the bottom up. A second exemplary organization, Friends of the Earth International, is a federation of autonomous environmental organizations from all over the world whose members, in 70 countries, campaign on the most urgent environmental and social issues of our day, while simultaneously catalyzing a shift toward sustainable societies. They believe the lending policies of the World Bank, and exploitive free trade agreements between rich and poor nations, are leading to a global system of unsustainable production and consumption that benefits giant corporations but fails people.

If we are to persuade others to join collective efforts such as these, we must understand what inspires people to action. In my own case, I was moved to action by a vision of how things could be different and I think that is what motivates most people.

Nationalists are also aware of this powerful motivational force. They control our vision of the future by limiting what we see. Our election process is a classic example of this. In our last race, neither Nader nor any of the third party candidates were given access to the media. As a result, we had a non-debate between two wealthy pro war representatives of capital. Concepts that could affect our quality of life such as socialized medicine, peace, education and options to the wage system were either narrowly defined by the democrats and republicans or not brought up at all.

The internationalists view of the world citizen is kept completely out of view of the American public, consequently, the Nationalist are able to mutate our love for our fellow humans into love for only United States Citizens, and then into fear of the “other”. We can witness this manipulation by examining how our government nurtures camaraderie among soldiers in the Iraq War. Soldiers routinely engage in acts of kindness and self-sacrifice toward each other (risk their lives to save a fallen soldier, look out after the weaker soldier, etc.) but rarely do they extend this kind of support to the Iraqi people whom they were sent to liberate. Even though many soldiers now realize that they were misled by deceitful propaganda and are now fighting an illegal and unjustifiable war of aggression they return day after day to the battlefield. They do this not because of the necessity of the war, but because of the camaraderie the government has nurtured within their military “family”. Our challenge as artists is to nurture this same camaraderie to a point where citizens of all nations can break from the narrow confines of nationalistic love to international love and compassion for all.

Depicting positive solutions to all forms of injustice, war, poverty and environmental waste must be recurring themes in our art. Organizations such as Friends of the Earth International and Food First, exemplify such solutions, but because they threaten the status quo, our corporate sponsored media intentionally ignore them. As artists, we must propel such examples of a more intelligent and compassionate way of life into the public consciousness.

An increase in the number of images persuasively reflecting an alternative to Nationalism will undoubtedly be met with aggressive, divide-and-conquer tactics. John Ashcroft, the nation’s former top cop, stated, “Those who oppose the Patriot Act only aid terrorists, erode our national unity and diminish our resolve”. Since the passage of the Patriot Act, some artists critical of America’s military aggression have lost their teaching jobs, others have been threatened with jail and still others have censored themselves out of fear. Increasing numbers of Arab or Muslim artists, as well as artists from countries not supporting U.S. policies, have been denied visas. Regardless of these efforts to silence criticism and censor the international perspective, the majority of United States artists have not been intimidated.

Many of us gather courage and resolve from remembering examples of international solidarity such as the dockworkers from Japan, Canada and the United states who risked their jobs by refusing to un-load the cargo ship, Neptune Jade. England had just privatized its ports, fired it’s union workers and hired scabs to load the cargo. The dock workers solidarity was so strong, the shipping company could not unload its cargo in 3 countries and finally had to change the ship’s name in order to get the cargo unloaded. Another example of inspirational collective action is the recent factory take-overs in Argentina. There, the economy crumbled under the weight of foreign debt and a corrupt government, leaving the workers unpaid and without jobs. The ex-employees bravely reoccupied a number of plants and began to operate them themselves. They shared the profits and dictated their own working conditions. The cooperative movement in Venezuela is also an up-lifting experiment in self-organization. To date, there are approximately 58,000 cooperatives, each one set up with a small government loan, democratically operated and the profits are divided among the members however the members see fit. The small government start-up loans are paid back not to the government but to another beginning cooperative, thus continuing the enrichment of the Venezuelan people rather than the government. Historic individuals such as Paul Robeson can also inspire strength. We can gain inspiration from remembering the internationally famous singer, actor and an All American football player, Paul Robeson, who, at the height of his popularity, was stripped of his passport and blacklisted because of his support for socialism. He tenaciously held onto his moral beliefs refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee. Such visions of international solidarity, factory take-overs, sharing of resources, successful experiments in self-rule, and sustainable living practices can inspire us all as we take our art on the offensive.

Volunteers Needed

As for contemporary artists who have never raised their brushes in self-defense or in the defense of others, I would like to encourage you to lend your specific talents to envisioning a better future. Many artist friends have responded to this call by claiming that their form of expression is not suited to the requirements of effective propaganda, but this excuse is usually not founded in history. Artists of all stripes as unlikely as Mark Chagall, Joan Miro, Alice Neal and Jackson Pollock have all made artistic contributions to social struggles. Often the artist least expected to respond politically creates the most influential work. Other reluctant artists have told me that they did not feel qualified to design the future. They prefer to leave that job to more knowledgeable or politically aware persons. But this kind of abrogation of civic responsibility is characteristic of what has contributed to the demise of our democracy. The ominous proliferation of nuclear weapons and life-threatening environmental degradation proves that the policy of non-involvement is not working. It is paramount that we all take part in shaping the future.

Artists, in general, are resourceful, have a healthy intellectual curiosity, value justice and are highly suspicious of dogma. Although many do not publicly espouse their beliefs, they usually possess sound values—share the wealth, protect our natural resources, make love not war. We have developed our expressive skills and often view the world from a unique vantage point. This artistic perspective, often coming from our deep unconscious, can provide insights crucial to motivating, informing and problem- solving.

At this time in history, the survival of our species is dependent on learning how to cooperate. Our enemies, who profit from capitalism, racism, and war, will try to mislead us, distract us, divide us, and destroy our organizations. Our job as artists is to create images that expose the ugliness of the exploiters, but, equally important, we must show viable alternatives to a better future.

— Doug Minkler 2005